10th Anniversary of Denton’s First Bike Plan

April 22, 2022

Denton’s first bike plan, adopted on February 21, 2012 by the Denton City Council, recently passed its ten-year anniversary. What led to the creation of the plan, what was in it, how well has it been implemented and what can we expect in the next ten years?

Residents Push for a Bike-Friendly Denton

The push for Denton’s first bike plan began around 2009 by a group of residents including Howard Draper. A few years earlier, Draper started challenging himself to replace car trips with bicycle trips, eventually selling his car and living car-free.

Draper quickly noticed a lack of attention to the issue of people in automobiles striking, injuring and sometimes harassing or assaulting people traveling by bicycle. These incidents often were not mentioned in the police blotter or the local news. To bring more attention to these and other issues, he created a blog called Bike Denton to highlight crash trends and other cycling topics.

Bike Denton post about a 2011 hit-and-run.

Concerned about their safety, residents began pushing for bike lanes and policies to improve safety for people traveling around Denton by bicycle. Through the advocacy of Denton City Council members like Dalton Gregory, the City Council passed a Safe Passing Ordinance.

In spring of 2010, city traffic engineers gathered resident input on bicycle routes and infrastructure. That fall, a consultant was hired to develop Denton’s first bike plan in coordination with local stakeholders. Throughout 2011, the City gathered public input to guide the plan’s development.

Residents showed their strong support for adoption of the Bike Plan. Several attended a City Council meeting in September, 2011 to speak in support of allocating funding in the annual budget to implement the Bike Plan. Among the speakers were an elementary school student and a senior woman who said she had biked 10 miles from her home in Robson Ranch to attend the meeting.

Read: Advocates Call for Bike Plan Jumpstart Funding (Bike Denton, 9/7/2011)

Several months and meetings later, the Denton Bike Plan draft was ready for consideration by the Denton City Council in February, 2012. It was approved unanimously.

Denton City Council members voting to approve Denton’s first bike plan in February, 2012.

The Plan

Denton’s Bike Plan identified nearly 35 miles of projects to be implemented within 1-3 years of the plan’s adoption. An additional 35 miles were planned for implementation within 3-10 years.

Of the 70 miles of proposed projects, approximately 19 miles were planned as bike lanes. Most proposed projects were shared streets, urban shoulders and wide curb lanes.

Design examples from the 2012 Denton Bike Plan.

Unprotected facilities like shared lanes and wide curb lanes were the norm in U.S. bicycle infrastructure at the time. It was not until 2007 that the U.S. saw its first parking-protected bike lane.

In 2011, the first engineering guidance on protected bike lane construction was released in the Urban Bikeway Design Guide by the National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO). However, most traffic engineers rely on designs recommended by the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO). AASHTO’s Guide for the Development of Bicycle Facilities, last updated in 2012, discourages protected bike lanes due to lack of U.S. based safety research, since no protected bike lanes existed when the guide began development.

Read: The Rise of the North American Protected Bike Lane

The rough cost estimate for Denton’s planned projects totaled $2.6 million and did not include costs for right-of-way acquisition, design, surveys, traffic signals or road modifications beyond paint and signage. The Denton City Council voted to allocate $200,000 for project implementation each year in Denton’s annual budget.

With funding of $200,000 per year, the first 10 years of proposed projects would take 13 years to complete, assuming all costs remain within the projected amounts.

Bike Lanes Planned for First 1-3 Years

The 2012 Bike Plan proposed the construction of 12 miles of painted bike lanes and nearly 23 miles of lanes shared by bicycle and motor vehicle traffic. Only the 12 miles of painted bike lanes are included in the following map.

Bike lanes planned for the first 1-3 years.

Bike Lanes Planned for the Following 3-10 Years

Approximately 7 miles of painted bike lanes and 28 miles of shared lanes were planned for years 3-10 of the Bike Plan. Only the 7 miles of painted bike lanes are included in the following map.

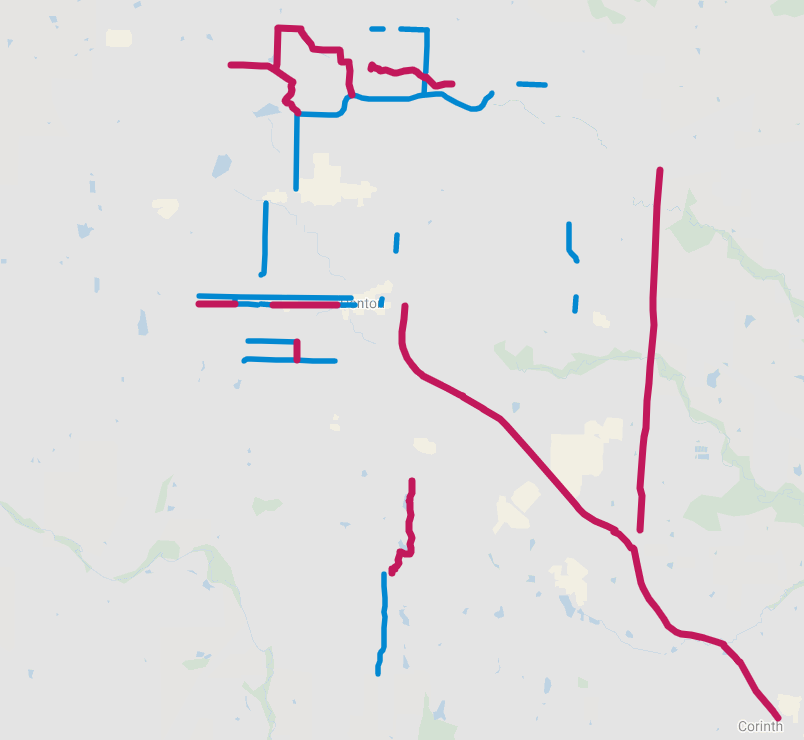

Painted bike lanes planned within the first three years (red lines) and 3-10 years (blue lines).

The implementation plan of the Bike Plan included the following action areas:

Organize a bicycle program;

Plan and construct needed facilities;

Promote bicycling and walking;

Educate bicyclists and the public;

Enforce laws and regulations.

The Implementation

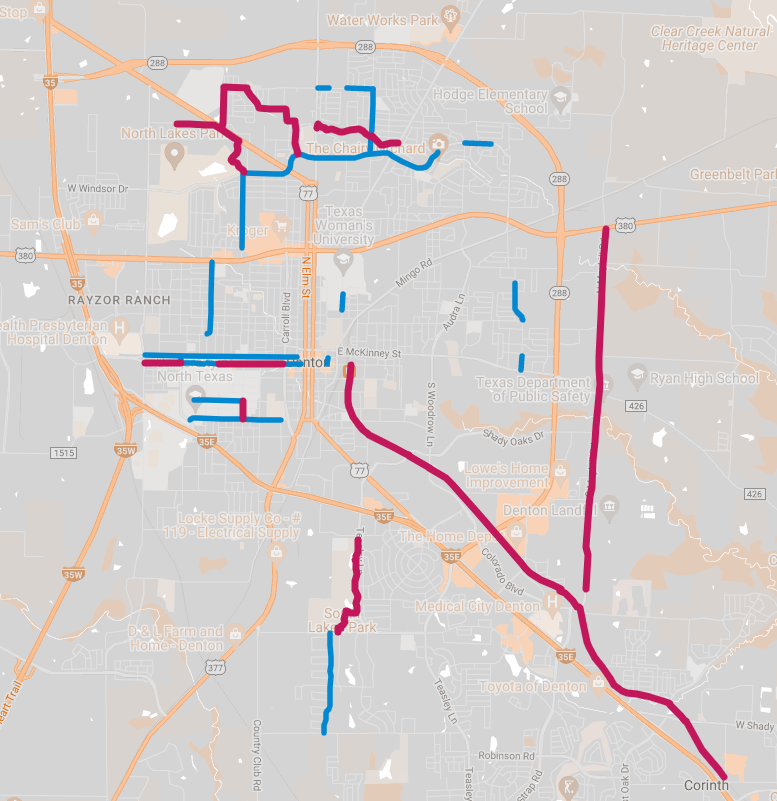

Existing infrastructure. Blue lines are paint-only bike lanes. Maroon lines are trails, side paths and protected bike lanes.

The City quickly began work to install bike lanes on portions of Oak, Hickory and Windsor. Discussions of a route between the UNT campus and DCTA station along Sycamore Street were also discussed in 2012.

In early 2015, Denton hired its first Bicycle & Pedestrian Coordinator, Julie Anderson, to ensure that action areas of the bike plan were implemented. The creation of this coordinator position was recommended in the bike plan.

Every fall, Anderson presented to Denton’s Mobility Committee on how the $200,000 bike fund would be allocated each year. She initially focused on implementing low-hanging fruit like installing “sharrows” and shared street signage before moving on to more challenging projects like bike lanes and side paths, which would require more funding.

Proposed bike projects presented to Denton’s Mobility Committee in 2017.

The Highs

Following the adoption of the bike plan in 2012, Denton took several steps toward making the city safer and more friendly to people traveling by bicycle.

Denton’s Bicycle & Pedestrian Coordinator enacted several goals outlined in the action areas of the bike plan including:

Annual city bike rides to highlight new infrastructure and gather public input.

Bike Month activities, including Bike to Work Day and CycloDia, Denton’s first Open Streets event.

Manual traffic counts to gather data on bicycle traffic volumes along certain streets.

Safe cycling classes for residents and bicycle safety presentations for elementary school students.

Public awareness campaigns about Denton’s safe passing ordinance and pedestrian safety.

Cycle with the City in 2015 (Image from Bike|Walk Denton Facebook page)

CycloDia open streets event in 2017 (Image from Bike|Walk Denton Facebook page)

Advertisement shown in movie theaters about Denton’s Safe Passing Ordinance.

Construction of off-street paved trails provided residents with the option to bike to destinations that would otherwise be challenging or dangerous. The Cooper Creek Trail extension in north Denton, funded through external grants, connects residents to a school and three city parks.

Cooper Creek Trail extension in north Denton.

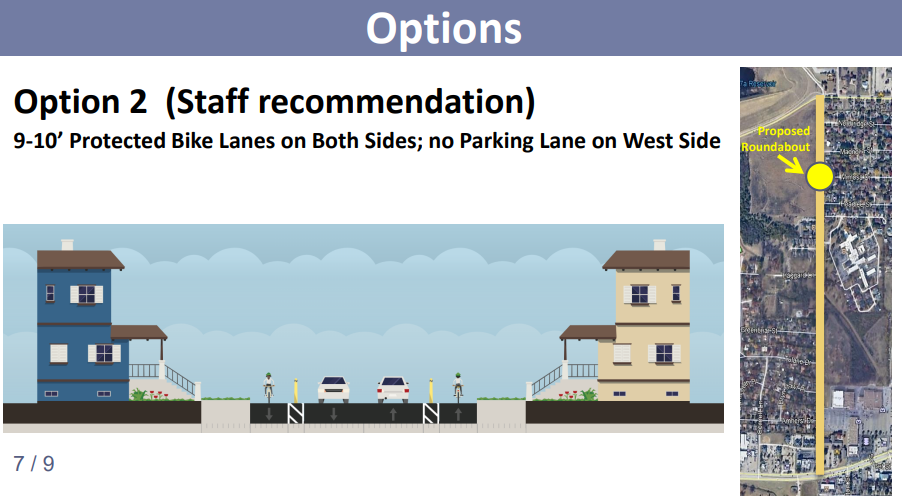

In October, 2019, the Denton City Council approved a bollard-protected bike lane design for Hinkle Drive to provide residents with a comfortable route to a grocery store, movie theater and other retail. This was an upgrade over the previous unprotected bike lane located between a parking lane and moving automobile traffic. As of April, 2022, however, the bollards still have not been installed.

Slide from a staff presentation to Denton City Council on October 8, 2019.

Dedicated bike lanes were added to wide roads like Windsor, Eagle and Malone so that people on bicycles would not have to ride in the same lanes with motor vehicles.

The Lows

While Denton took steps forward during the past ten years, there were also setbacks.

Projects Abandoned

In 2009, residents in the Southridge neighborhood requested bike lanes along Pennsylvania Drive to improve safety for people outside of automobiles. County Commissioner, Hugh Coleman, committed $50,000 in county funding for the project. However, other residents along Pennsylvania Drive blocked the safety measure in 2012, and the bike lanes were not installed.

In 2017, dedicated bike lanes were proposed along Ector Street to improve safety for people biking and walking and to reduce speeding. However, residents rejected the safety measure in order to retain city-funded automobile storage despite an above-average supply of private off-street parking on drives along the street.

Striped lanes for automobile storage were installed instead of bike lanes.

Ector Street in 2016.

At some point between 2018 and 2021, the City restriped Avenue A between I-35 and Eagle Drive without installing the planned bike lanes.

Avenue A / McCormick in 2021.

Despite 2017 plans to add bike lanes to North Texas Boulevard on the UNT campus, bike lanes were missing from designs released in 2021 for an upcoming construction project on the street. Due to lack of public discussion, it was not clear whether the bike lanes had been deliberately axed from the plans or simply forgotten.

Projects Delayed

Some bike lanes were hotly contested, especially along W Oak Street and W Hickory Street, where some residents and business owners advocated for retention of city-funded automobile storage over improving safety for residents and customers traveling by bicycle.

Completing a two-block gap in the W Hickory Street bike lane required two years of meetings after concern that repurposing approximately two parking spaces per business for safer bicycle access to the area would harm nearby businesses.

A 2018 parking study indicated that an average of 1-2 of the 24 spaces on the south side of W Hickory Street were occupied by possible customers at any given time, while an average of 22 of the spaces were occupied by people headed toward the UNT campus.

To resolve the stand-off, Avenue A and part of Mulberry was converted to a one-way street so most of the automobile storage could be relocated nearby to make room for the first protected bike lane in the city.

W Hickory Street, Denton’s first protected bike lane.

New Bike Lanes at Risk of Removal

In at least one case, newly-installed bike lanes were at risk of removal. Barely three months after bike lanes were installed on Eagle Drive in 2016, then-Mayor Chris Watts requested that staff re-assess the project due to perception that almost no one was using the bike lane and that motor vehicle delay had increased.

To add the bike lanes on Eagle Drive, the four-lane road was converted to a three-lane road with two main travel lanes, a center turn lane, and a bike lane on each side. Since 2012, the Federal Highway Administration has promoted this type of road reconfiguration as a proven way to reduce traffic crashes by 19-47% while maintaining the same effective road capacity.

A resident pushed back on Mayor Watts’ concerns by emphasizing that improving safety was the focus of the project and that people were indeed using the bike lane. A staff study showed little change in motorist travel times and a 302% increase in pedestrian volume after project implementation.

The bike lanes ultimately remained intact.

Eagle Drive bike lanes in 2019.

The Results

The 2012 Bike Plan had two goal statements aimed at making the City of Denton a better and safer place to walk and ride bicycles:

Goal #1: Increase the awareness and acceptance by local policy makers, planners, engineers and motorists in Denton of bicycling and walking as viable modes of transportation and legitimate users of the publicly-financed transportation infrastructure.

Goal #2: Promote the increased use and safety of bicycling and walking in Denton through the development of a comprehensive yet financially feasible system of bicyclist and pedestrian facilities, support facilities and programs.

Its objectives were:

Implement portions of the Pedestrian and Bicycle Linkages Plan each year as opportunities arise and as budget allows.

Establish Denton as a bicycle activity and sport destination within the next 10 years.

Promote adherence with traffic laws by bicyclists and pedestrians in Denton.

Reduce the number of bicyclist and pedestrian traffic accidents.

Promote Coordination among implementing agencies in regards to the Pedestrian and Bicycle Linkage Component.

Provide a regular program of bicycling proficiency and safety each year.

Provide a regular program of bicycle and pedestrian safety information to motorists and the general public in Denton each year.

Strategically pursue funding for facilities and program assistance.

Promote public/private partnerships in development, implementation, operation and maintenance of bicycle and pedestrian facilities.

There was visible progress toward many plan objectives between 2015 - 2017. Progress stalled, however, beginning in 2018 after the departure of the Bicycle & Pedestrian Coordinator and the Director of Transportation. The City dissolved the Transportation Department and moved the Bicycle & Pedestrian Coordinator position to Capital Projects, which oversees traffic engineering and operations, streets and drainage.

The City largely ended implementation of objectives relating to programming and education after moving the Bicycle & Pedestrian Coordinator position to Capital Projects. Focus shifted primarily to implementing infrastructure.

In addition to the plan’s stated goals and objectives, the success of a bike plan is often measured by ridership and crash rates. A well-executed bike plan should increase ridership by connecting people to where they need to go while also decreasing crash rates and injuries.

Ridership

Denton’s first Bicycle & Pedestrian Coordinator set long-term ridership goals and organized manual bike counts with volunteers to measure how many people were riding along key routes. Some count locations already had bicycle infrastructure, while others had infrastructure planned. The goal was to assess the success of infrastructure projects by measuring ridership both before and after project implementation.

Strategic outcome from the 2016-2017 Denton Budget, p. 56.

After the first Bicycle & Pedestrian Coordinator left in January 2018, the city stopped setting ridership goals or counting bicycle traffic, so ridership numbers and project impacts are unknown.

Crash Rates

Without ridership data, it’s impossible to determine crash rates. However, between 2013-2021 Denton averaged 29 reported crashes annually involving someone on a bicycle.

Data retrieved from TxDOT CRIS Query database on April 21, 2022.

Of the 274 reported crashes between January, 2012 and April, 2022 that involved a bicyclist, 91% occurred on a roadway that either does not have a dedicated bicycle accommodation or did not at the time of the crash. Of the estimated 25 crashes along roads with a designated bicycle facility, 100% occurred along roads with unprotected bike lanes or intersections.

Nearly half (48%) of reported crashes involving a bicyclist occurred on a TxDOT roadway including University Drive and Loop 288. These roadways are designed to prioritize motor vehicle speeds and are wide, fast and feature oversized, dangerous intersections. Despite the lack of safe infrastructure, people traveling by bicycle are forced to cycle across or along these roads in order to access their daily needs.

Connectivity

Bicycle infrastructure is only useful if it connects people to where they need to go. No matter how comfortable it is, a bike lane that connects to nothing else is not useful and is unlikely to increase ridership.

Here is the connectivity of Denton’s existing bike lanes and paved trails.

Painted bike lanes are in blue. Trails and protected bike lanes are in maroon.

The actual connectivity of Denton’s bicycle infrastructure is less than the map makes it appear.

Drivers frequently block bike lanes like Highland Street and Oakland Street, making them dangerous or impossible to use. Many intersections interrupt connectivity by forcing people on bicycles to merge with much larger motor vehicle traffic in order to turn left or, in some cases, to continue straight.

Truck driver blocking the contraflow bike lane on Highland Street, forcing a student to ride into oncoming traffic.

Seven drivers blocking the contraflow bike lane on Oakland Street (April, 2022).

On W Hickory at Avenue C, people on bicycles must merge with motor vehicles in order to continue straight to the bike lane on the other side of the intersection.

Denton’s Updated Bike Plan

On March 22, 2022, the Denton City Council unanimously approved an updated bike plan, which was included in a larger Mobility Plan update.

Throughout the update process, which began in 2019, city staff suggested a move away from sharrows as bicycle infrastructure and a move towards infrastructure with more protection and comfort so more people can use it.

In a 2017 phone survey about bicycling, City of Denton residents were asked to indicate their comfort level bicycling in Denton. Only 16.4% of respondents indicated at least some willingness to bicycle in the same lane as motor vehicle traffic, while 38% of respondents indicated that they enjoy bicycling but are too afraid to ride.

Denton survey respondents self-identified as one of four types of bicyclists.

Since the adoption of Denton’s first bike plan in 2012, bicycle facility design has shifted substantially in the United States. In 2019, the Federal Highway Administration released their Bikeway Selection Guide, which emphasizes that bicycle networks should be safe, comfortable and connected.

In 2021, the Texas Department of Transportation released new bicycle design guidance that moves away from shared lanes towards better separation, safety and comfort for people traveling by bicycle. The guidance suggests that bicycle facilities should focus on the large portion of “Interested but Concerned” users.

Image from Page 3 of TxDOT’s State of the Practice in Bicycle & Pedestrian Accommodation

Read:

High-Quality Bike Facilities Increase Ridership and Make Biking Safer (NACTO, 2016)

Why Cities are Investing in Safer, More Connected Cycling Infrastructure (Urban Institute, 2022)

Denton’s updated bike plan follows suit with the new standard of designing for the “Interested but Concerned” user. The update also suggests a focus on connectivity and usefulness, not just mileage.

Looking Forward

According to Dutch CROW Design Manual for Bicycle Traffic, successful bicycle infrastructure features the following principles:

Cohesion - Connecting origins and destinations. Cycling from anywhere to everywhere.

Directness - Creates short and fast routes. Minimizes detours.

Safety - Avoid differences in speed and mass. Separate modes where possible.

Comfort - Minimal stops or nuisance.

Attractiveness - Attractive: Clean, green, water, open, quiet. Unattractive: Dark/unlit, traffic, congestion, loud.

Cities that prioritize funding and rapid implementation of safe, well-connected bicycle routes have seen large increases in bicycle ridership. Recent examples include Seville, Spain and Paris, France. Seville’s ridership spiked 452% in just three years after rapid implementation of a low-stress bicycle network. Ridership in Paris, France increased by 54% in a single year thanks to heavy investment and rapid implementation of protected bicycle infrastructure.

In 2020, voters in Austin, Texas approved a $460 million bond for active transportation projects including sidewalks, on-street bike lanes, urban trails, Safe Routes to School and Safety/Vision Zero. Portions of the bond are expected to fully fund the remaining 200 miles of Austin’s 400-mile All Ages and Abilities Bicycle Network by the targeted completion date in 2025.

After creating a plan, a city must implement it. To keep costs lower, Denton has primarily added bicycle infrastructure only when a street is being resurfaced. For a street resurfaced just prior to the Bike Plan’s adoption, this means it could be 15 years or more before the bike lanes are installed.

How quickly a plan can be implemented depends heavily on how much funding it receives.

Since 2012, more than $83.6 million in bond funding has been allocated to widen approximately 8.7 miles of existing roadways in an attempt to improve travel times for people in automobiles. Over the same period, no dedicated bond funding has been proposed in an attempt to improve safety for people traveling by bicycle beyond adding 10-foot sidepaths to road expansion projects where automobile travel is the priority and bicycle and pedestrian travel are secondary.

When the Bike Plan was adopted, Denton designated a line item of $200,000 in the annual budget to implement the plan. The Portland Protected Bicycle Lane Planning and Design Guide, released in 2021, estimated that installing protected bike lanes on an existing road can cost anywhere from $73,000 per mile for a painted, parking-protected bike lane on a one-way street to $1.1 million per mile for a bike lane separated from automobile traffic by a concrete island.

Concrete island protected bike lane (Image source: Portland Protected Bicycle Lane Planning and Design Guide)

Just $30 million in bond funding could build a core network in Denton of at least 30 miles of All Ages & Abilities (AAA), high-comfort bicycle facilities that would provide more Denton residents with the option to make more trips by bicycle.

Concrete island protected bike lane (Image source: City of Austin, Texas)

Will we fund and implement Denton’s new bike plan so it takes decades before Denton has a useful bicycle network? Or will we fund it for rapid deployment to more quickly provide Denton residents with an affordable, healthy, quiet and clean transportation option to travel to where they need to go?